How I survived a war between Germany and Cuba

The little known war between Germany and Cuba happened in my childhood home. It was a two-bedroom apartment on Howard St, the northernmost East-West arterial in the city of Chicago. Rogers Park is known as the most diverse neighborhood in the city of Chicago. I was born at a time when the neighborhood was changing from predominantly white and Jewish, to a neighborhood of Black Americans and immigrants. I was an off-white kid, in a mix of other off-white, off-black and black kids. White kids, in my mind, were only in the suburbs. In the city, we were a rainbow of skin tones and ethnicities.

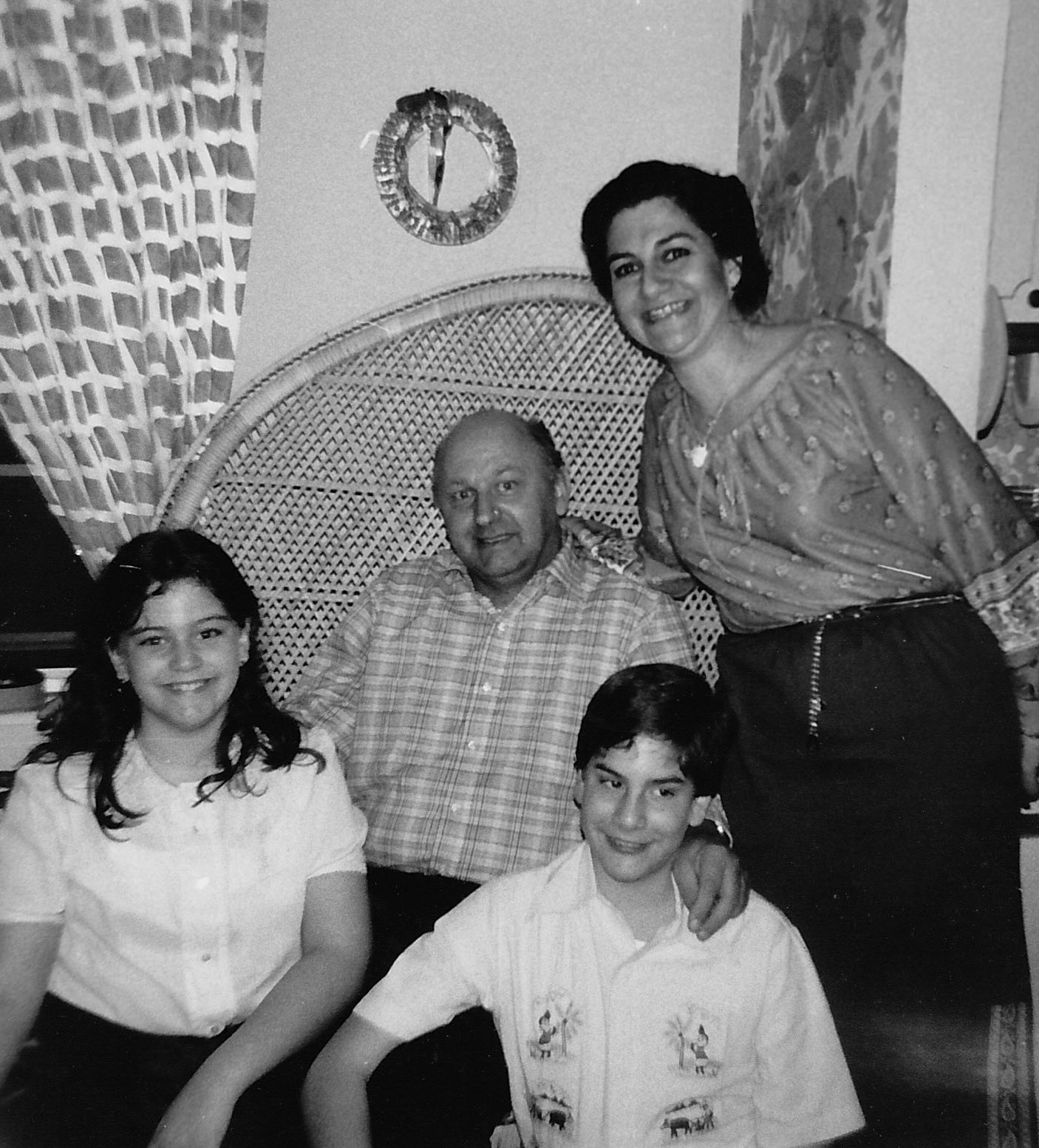

As a child, I thought we were a typical family. My bratwurst-skinned father was a quiet, hard-working, old school violin maker and my olive-skinned mother was a fiery, hard-working nurse, house keeper, and family feeder. I had friends of Greek descent, Mexican descent, and several Black girlfriends whose parents had similar roles, but the difference was that both of their parents were of the same ethnic background who shared a culture, a religion, and skin color.

The battles of this war were infrequent but explosive. The silence between these battles were just as deafening. In a world where Germany didn’t speak Spanish, nor Cuba speak German, the use of English – their second language – was fraught with miscommunications and misunderstandings. My brother and I were the collateral damage of these battles. Whether the battle was about the long-distance phone bill – where Germany ripped the kitchen phone out of the wall or about Germany driving his cute receptionist around while leaving his wife, who couldn’t drive at the time, and children to take the bus, the yelling, the pan throwing, the slamming, always ended in silence.

Today, I think about my fellow rainbow Americans. We are the group that acknowledges our differences. We fight for laws and policies that will take care of us regardless of our differences. We seek unity. We seek justice. We seek equality. We want to speak softly and respectfully. We want to listen. We strive for understanding despite the difficulties in finding middle ground.

I sometimes felt that if I wasn’t born – then Cuba and Germany would never have gone to war. Cuba wouldn’t be a stressed out mother cooking leiberkäse and potato dumplings. Germany would continue living his quite bachelor life, focusing on his craft. Family gatherings wouldn’t have been strange – the island of Cuba amidst a sea of Germans in Chicago or a German stump surrounded by a forest of Cubans in Miami. As a child, I could see and feel the tension the odd parent out felt when I was with my relatives. Granted, I can only recall one time that Germany went to Miami and vowed to never go back because he couldn’t stand all the yelling.

A few years ago, when I shared my background with a Diné friend, he told me I was a type of ambassador. I thought about that observation. He added that as a white-passing, ethnically ambiguous, educated woman, I could step inside multiple world views. I could listen and help negotiate differing views. I could write about my observations.

I survived the wars between Germany and Cuba because of the good times. Summer vacations were car-camping adventures led by the German quest to explore National Parks. Cuba was the eager co-pilot who also appreciated nature. With roles intact, there were no wars on those car-camping trips, Cuba and Germany were allies.

Those external wars between my parents weren’t frequent. These wars didn’t physically separate our family. For me, though, there was emotional separation. There were years I hated my father. For only reserving Sunday afternoons for his biological family. For putting his religion’s “brothers and sisters” before his family. For making our family celebrate birthdays and holidays away from our home and without him. For telling me I wasn’t German enough. My angst towards my father melted away when he helped me move cross-country to San Francisco when I was twenty-one. It was the first time we ever spent time alone. It was the first time I saw myself in him – or the other way around. It was the first time I told him I loved him – and the first time he told me he loved me.

I have always loved Cuba. Despite my teenage and adult tug-of-war battle for independence from my Cuban mother – I resonate most with my Cuban heritage. Although my mother didn’t cook Cuban food when I was a child, I tasted and fell in love with Cuban food at my Abuela’s house, at the La Unica cafe on Devon Ave., and in Miami. Although my mother didn’t speak Spanish to my brother and me, unless she was mad, I learned Spanish by listening to my grandmother and my Cuban relatives in Miami.

I share these thoughts about differences today because I want you to know it isn’t easy. It isn’t easy to look past our differences to find common ground. It isn’t easy to try to speak someone else’s language. It isn’t easy to understand another’s point of view. It takes work. It takes a desire to want to look past the differences. It takes a desire to want to heal the wounds of misunderstanding and disrespect. I’m not saying you have to like everything. I’m not particularly fond of German food. I’m not close to my German relatives. I would rather visit Spain than Germany. But I respect my heritage. I have Cuban relatives whose political leanings are opposite mine, but I still love them.

And maybe that’s the message. If we open our hearts, without fear, but with love and trust, then maybe we can look past the differences that separate us and work towards a world where our similarities unite us.

Leave a comment